This seems to go along with Your Paper Andrew,Lectio Divina has been a huge influence in how I enact Meditation & Reading. The Experience of the two has gone a long way to /for healing & maturing as Stranger in a Strange Land.

Thanks, Michael!

Hey Everybody,

Here is my attempt to elucidate a practice of what I am calling “heart-reading,” which is based on transpersonal feeling, as opposed to emotion or sentimentality or Wildean sincerity (“all bad poetry is sincere”). I am also trying to extend (or make more accessible?) Bloom’s argument that reading involves one’s “daemon,” a Greek word for an “attendant spirit.” I am saying that this daemon is not just a metaphor, but is ontologically real. Literature, like meditation, can get one or put one in touch with said daemon. Anyways, the piece below is my attempt to “theorize” about what I value in regards to aesthetics and the daemon, both in the act of criticism as well as the act of writing poems.

'This deity, daemon, is one’s own aboriginal self, as well as one’s compass, and is ontologically real. Quixotics is the attempt to listen to and honor the daemon; in doing so, better literature and criticism will develop."

“One’s own aboriginal self”…there’s a Artifact I Desire to cultivate!

Here is a book review I posted today on Medium, of Joseph Massey’s new collection, A New Silence. The review touches on some of the things we’ve talked about inside and outside this thread, in terms of poetry, spirituality, phenomenology and consciousness. If you read it, I hope you enjoy it.

I love “Quixotics,” @AndrewField81. That is a bandwagon I could get on with!

I only point out that the original Quijote (who, granted, Borges argued could be originally rewritten) was not some kind of pure aesthete, but rather was driven by his ridiculously excessive and fantastical idealism. At the risk of gesturing toward imaginary windmills: he wants to be the hero, save the princess, slay the bad guy. A quixotic aesthete should be all about ethics, I would say.

Rather than attempt to banish the question, “Is X good or bad, or in what ways is it both or neither, for my/our/others’ human/terrestrial/cosmic life?” (i.e., ask ethical questions of art) I believe Quixotics should offer the most unreasonable of ethical aesthetics imaginable. It should involve an ethics of the impossible.

I get the feeling that when you talk about “ethics” you mean something very different than what I resonate with in the same word. I don’t believe we should demote or banish the ethical dimension, or fall back on truisms (true as they are) such as the Golden Rule, when it comes to real art; there is too much at stake. The consequences of ignoring the ethical are too grave in a work of any power.

How can you truly evaluate a poem without considering its effect on life? Is the poem a pure object of abstract beauty, which has no consequences worth considering in the world? Only what it makes one feel? Its transcendence?

For me ethics is aesthetics in the sense that ethics describes what I would call the aesthetics of relationship. When we say something is “bad,” I would point out that perhaps we mean that it feels bad, causes disgust, thus we perceive it as “ugly,” uninteresting, or mediocre. This gets very subtle, because some kinds of “ugliness” — the violence of a crucifixion, for example — can actually be transfigured, as in Renaissance art, into aesthetic objects of exceptional beauty. We transmute suffering aesthetically. Is that not an ethical act?

I don’t see the point in removing art from the real world — where human and other sentient beings live in proximity and we (reflective, self-authoring ones) must treat each other and our environs in ways that allow things to work out, promote life. How is art separate?

I am guessing that your argument against the inclusion of an ethical axis in integral literary criticism has something do with (in your experience) “ethics” referring to a certain pattern of dismissal and exclusion of the aesthetic axis under the rubric of ‘postmodernism’ (‘1st tier,’ ‘green meme’ in integralspeak) and through such practices as Foulcauldian analysis, etc. — but not Ethics per se, in a real philosophical sense.

How a work of art makes one feel, and by extension and implication, its effect in the world (since feelings drive things), is of inescapable ethical concern, it seems to me. That’s not just my idiosyncratic uniqueness talking! It’s life. The human heart is where we know the ethical. I say ‘spirituality’ is worth shit if it doesn’t involve both ethics and aesthetics. If we’re all geniuses and could only fully express our incommensurable individuality — would that be enough? Would we repair nothing of the world? Is that the grand Quixotic quest?

Is Beauty as beautiful as it could be if it is not also True and Good?

Marco!

I enjoyed reading your response. I am off work soon, and when I get home I will try and respond to your comments. But in the meantime, I wanted to say that for some time I was really into ethical criticism, and even wrote an essay about it, using mostly Martha Nussbaum’s work as my guide:

http://www.thethepoetry.com/2014/01/what-becomes-of-us-as-we-read-ashbery-and-ethical-criticism/

Nussbaum is great in a lot of ways. What changed my mind in regards to ethical criticism was reading Charles Altieri. He used to have his own website where he posted many of his papers for free, but it seems like he took it down at some point. Anyways, I’m going to think about what you said, and do my best to write back soon. Thanks!

I have to confess here that I have never read all or even most of Cervantes’ Don Quixote. I don’t know why exactly - I’ve been meaning to read the whole thing for years. Maybe I needed to talk about “Quixotics” outside that book, so as not to be somehow utterly contaminated by it, at least initially, when I started writing about the idea. At any rate, I utter this confession so that what I say next is taken with a grain of salt, as I still need to read that massive intertextual tragedy/comedy and first novel.

Having said that, I think what you are describing in a more bare bones way is a sort of quick summary of the character Don Quixote’s intentions - i.e. to be the hero, etc. That could totally be true. But think about these intentions. From what I remember, Quixote is so utterly transfixed and obsessed with romance novels that he imagines he himself is a character in a romance novel. It is so absolutely absurd, sad, funny, hilarious, ridiculous, tragic, etc. Yes, because he wishes to be a chivalric character in a romance novel, he wishes to check off all the task-boxes for being such a character: saving ladies, slaying villains. But what does ethics actually have to do with any of this? What is really being described, investigated, explored is the relationship between imagination and reality. The quick and dirty definition of ethics might be, a la Wiki, “moral principles that govern a person’s behavior or the conducting of an activity,” or also the study of such principles as a branch of knowledge. Okay, Quixote has wonderfully comic moral principles. But would anyone in their right mind use the study of moral principles to come to any understanding about the spirit and resounding life of Quixote? I think such a study would itself be utterly comic and absurd. I’m thinking right now of Malvolio from Twelth Night, the way he seems to wander into the play from another play. Using moral principles to come to any understanding of that novel is sort of like being Malvolio in Twelth Knight - there is a very egregious crossing of signals, a sort of mix-up that does not bode well for either moral principles or Cervantes’ enduring masterpiece.

I think I associate moral principles, in a way, with the God in Milton’s Paradise Lost - sort of boringly benign, uninteresting, yawn-inducing. Blake wrote about Paradise Lost, in “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell”:

Note. The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.

Artistic creation - and therefore the relationship between imagination and reality - has nothing to do with moral principles. Here is Blake again:

Energy is an eternal delight, and he who desires, but acts not, breeds pestilence.

I agree with this. I would love to hear your definition. I really think of ethics along the lines of “he who desires, but acts not, breeds pestilence.” I think most people justify their fears out of quasi-ethical concerns that are really just ways they escape becoming their actual quixotic selves. All sentient beings have their own incommensurable dignity, of course. And ethics is a real and important dimension of life, as is politics, justice, etc. But at this point in my own life, I’m willing to err on the side of Milton’s Satan. I think much of our ethical concerns are ways we disguise, malform, repress, and even mutilate our actual unconquerable and never-ending desires. I think talk about ethics in this sense just confuses the issue. Marianne Williamson’s oft-repeated quote is relevant here:

Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our Light, not our Darkness, that most frightens us.

Richard Rorty argued for a long time that projects of self-creation, which we can think of as aesthetics, and projects of human solidarity, which we can think of as ethics, are both absolutely important but forever irreconcilable at the level of theory. There is no practice without a theory behind it, so this argument has massively interesting implications. While there are many aspects of Rorty’s philosophy that I utterly disagree with, I wonder if he was somehow more right in this regard.

While I used to be into John Dewey, as well as Mikhail Bakhtin, and their fascinating interest in the relationship between art and life, I have to say that at this point I think there really is an important difference to be honored between art and life, though there are similarities as well. Since a book I have been reading talks directly about this, let me share an excerpt (from Angus Fletcher’s Colors of the Mind):

It will be objected that the aesthetic rendering of the [processual aspect of experience, i.e. being-in-becoming] is mere illusion. One answers that the work of art resembles life and nature, but not in a miming sense. Rather both life and the art work are phenomenological experiences. As more than one author since Cervantes has suggested, the work of art (the so-called illusion) often forces us to see the limited degree to which life can be called “real”…The work of art exists, one might say, to illuminate such process-laden domains of human experience.

For something to illuminate something else - whether art illuminates life, or life illuminates art - there has to be a difference-in-sameness. If they were the same, how would they illuminate each other? If they were totally separate…and so on. Still, as a very passionate lifelong reader, I do not really find in “life” the sustenance I find in art. Others might feel differently, or much differently. For me, there is always a frustrating agon in life between thought and speech. By this, I do not mean like wanting to shout inappropriate things, but not being able to. I mean that life does not afford very many opportunities to really slow down (“chunk down and chunk slow” a la @johnnydavis54) and think and share one’s actual thoughts. We do not very often speak our thoughts fully - there isn’t time, or interest, or an audience, or space, or something. In art, there is that time and space and interest. If there isn’t, artists create that time and space. There is therefore not as much frustration in art between what we think and what we say, though there often is this frustration in life. Perhaps this explains why Aristotle’s “catharsis” is such a powerful idea - art is essentially a technology of and for freedom. The greatest art teaches us how to be free, in our innermost selves. Personally, I don’t see moral or ethical principles as relevant in this context, except in a pale, obvious and uninteresting way. Maybe I’m wrong.

It would seem I need some assistance here lest I become too confused.

Does art teach us to be free by producing it, or by engaging it? If it is the former, does this mean that the artist is producing it only for themself? If they are, why should anyone care as no one will ever experience it. If it is the latter, then it seems that the assumption is that art is produced with at least some kind of other in mind. If that’s the case some “guide” of interaction with an other is essential, is it not? And whatever it is that guides our interactions with others is what we call ethics, is it not?

I have the feeling that I’m probably missing something very obvious or a very big point, or perhaps both.

I am about to leave to grab some food, but I wanted to share this article by Peter Elbow, a “composition theorist,” (someone who writes/thinks about the writing process). I would like to read the whole thing again, but I don’t have time right now. I read this when I was a graduate student, and I remember it had a big impact on me in terms of how we might think about an artist’s relationship to his or her audience. Here’s the link:

This is a good point, Andrew, and reminds me of Blake, who said, “ Those who restrain desire do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained.”

But of course ‘restraint’ must also be desired, more strongly desired than the primary desire being restrained. Perhaps this is a function of mere repression, but it could also be an outgrowth of a greater positive desire (e.g., ascending eros).

Kierkegaard suggests, in Either/Or, that there can be a “teleological suspension of the ethical,” in other words a value superseding moral principals, but he located this higher-order justification in the religious, whereas the ethical (as one’s sphere of concern widens) is a higher order than the aesthetic, which is mainly concerned with sensory experience.

The question deepens, however, when we combine (or conflate) the aesthetic with the religious (as Harold Bloom does). I personally regard literature as my “church without walls.” However, I believe that the definition of ethics in such a church would be quite different than it is in a conventional religious institution.

When you say…

… in fact, I believe you are making a strongly ethical statement about the nature of art. Your moral principle (guiding your aesthetic judgment) might go something like this:

Good art teaches us to be free; bad art enslaves us to the mediocrity of the crowd.

Does that resonate?

I am stumbling over the last sentence in this quote: “if they are [producing it only for themself], why should anyone care as no one will ever experience it.” I guess I don’t really understand the logic here - there is an implicit assumption that if an artist produces work for themselves primarily, then “no one will ever experience it.” Why would no one experience it? The assumption is that, if an artist produces work for him or herself, then they would not ultimately share it? But, if my interpretation is correct, that’s not true at all, i.e. there’s no reason why an artist producing work for him or herself would not ultimately share it. I had the chance to listen to the seriously wonderful podcast with Jeremy Johnson at dinner tonight, and there was some mention of Gebser’s relationship to some amazing artists (Picasso, Lorca, I think Rilke, too?). So take Picasso, for example. Did Picasso paint for an audience? I guess it depends on how you define audience. Was he painting for “the masses”? For “humanity”? I suppose in some very vague way, yes. But, was he painting for Georges Braque during the advent of Cubism, say? This, I think, would be a resounding “yes!” And, was he painting for himself, for his own self, for the sheer delight, fun, enjoyment, shock, astonishment, wonder, joy that came from allowing Spirit to work through him, in whatever language you use to describe this? Again, I think the answer is a very resounding “yes!”

But now we are in murky waters, relevant as well to @madrush 's posts earlier today about this whole ethics/aesthetics (feaux?) jousting. Clearly Picasso was painting, at least to some extent, for Braque - Cubism emerged (from what little I know about Cubism) to some extent from their collaboration. So (drumroll please): does this mean that ethics, the relationship between artist and other - Picasso and Braque, say, (or Emerson and Whitman, Langston Hughes and Alain Locke, Heidegger and Arendt, Lucy Lippard and Eva Hesse, John Cage and Shoenberg, Schuyler and Ashbery, all dead poets to all alive poets, and so on and so forth, ad nauseum) plays a role in strong aesthetic creation? And here is my answer, which is just a repetition:

ultimately, no, I don’t think so.

Why?

Quick detour into metaphysics (no, this is not an evasion!!!):

if the Self is actually all, the inner spark or light in the heart, the daemon, atman, what have you - then, at the deepest levels of existence, is there any sense whatsoever of actual separation, of separate bodies in time and space? Let me be clear here - I am not talking about separation in a psychological sense, as one separates from one’s parents, etc., which is totally necessary in one’s developmental arc. I mean it really purely metaphysically. At the level of metaphysics, separation is a total myth. It has nothing to do with what is real. It’s totally what Adi Da calls the “body-mind,” the “self-contraction,” essentially an illusion. If what I am saying has any validity, then how should we think about this aesthetics/ethics thing? I suppose, at levels we are trying to talk about, the distinction is, to me at least, pretty meaningless. The two are, a la Wittgenstein, one. BUT, if we are to talk about these things in the context of poems, then I still insist that ethics in our current age often produces weak readings that do not really account for the actual experience of reading a poem, as I’ve said a bunch (sorry for the repetition). We’ve had enough hermeneutics, I think; I think it’s time we return to the need and art of evaluation, which is a matter more than anything of the transverbal heart. Again, if we want to think about this clearly, take Whitman, who with Emerson and Dickinson essentially birthed American poetry. What happens in a good Whitman poem? Whitman sees the world and others capaciously. Why? It’s a question, fundamentally, of consciousness. His consciousness is expansive, capacious, gorgeous; so, he sees an expansive, capacious, gorgeous world. The inner comes first, always. If ethics prioritizes the other over the inner, morals over aesthetics, etc., there is a strange misunderstanding that happens, a sort of collapse, a pratfall. We should prioritize vision over morals - morals trundle after vision, follow in its wake. But vision, subjectivity, phenomenology, UL quadrant, interiority, et al. are primary, are “first philosophy.” Ethics comes after (take that, Levinas).

Apropos of nothing and everything, I Googled Adi Da and “bodymind” and found this video. I don’t know if I"ve watched it, but I love Da, and I’m sure it’s relevant somehow. His writings and teachings (and visual art!) would be a good topic for the Cafe.

As well you should. Due to where I am physically in relation to most of the IC participants, things often show up late, and instead of just going to bed as I should, I think I can just pop off a quick question or two and then call it a day. I’m not as young, nor as clear, as I once might have been. It’s not an excuse, just an observation. ![]()

The thrust of what was on my mind was art itself, I think, so you got it in spite of my muddlings. There are times when we write (or paint or sculpt or whatever … and some people never do it at all) for ourselves, with no intention of it ever being shared with anyone. This could be me journalling or it could be Chomsky writing a paper he knew was never going to see the light of day (from the Elbow article … which I enjoyed for its own sake, BTW). But I don’t consider either of these cases to involve art. They might lead to art at some point, or we might revisit them and extract something we could use in something we are producing that will be art once it is shared, but they aren’t examples of art, at least not in my mind.

But in answer to your question whether I think Picasso was painting (or anyone writes) for an audience, my answer would be a resounding “jein” (a mash-up of ja and nein). I don’t think he or any artist often (if ever) has a specific audience in mind, but whatever it is they are doing they want to share it. And at that moment others are involved, even if they are not specifically defined or identified. And I agree just lumping them in under some label like “humanity” or “the masses” is counterproductive.

Actually, I tend to agree with R.G. Collingwood who, in his autobiography, maintained that every work of art is really the answer to a question. It is conceivable that this question might be, “How much fun would it be to do this?”, but I personally think the questions being explored are deeper than that. And, knowing that others will engage the answer, if you will, is, to my mind at least, ethically tinged if nothing else, for the artist is really saying that their question is worth engaging, that is has some value, that the lives of those who engage it will be different in some (positive?) sense for the effort. Questions of value are to me ethical questions (not moral ones … they come much, much later).

While I couldn’t agree more than ultimately there is no separation, that’s not how most of us experience the world, and because we don’t we have to constantly interpret everything we experience. Even the mundane data fed to us by our primary sense have to be interpreted. For me hermeneutics is about interpretation so having a strong grounding in what that is and how it works and how we might do it better is a good thing. You see, I think your question, “What happens in a good Whitman poem?” is a hermeneutic question at bottom?

So, let me ask you: what you mean by “evaluation”. I think the word says what it means: “getting the value out of something”. As I mentioned earlier, values and ethics go hand-in-hand in my mind. So what values are we talking about? Who decides? May they be imposed or prescribed for others (whereby for me that is where ethics turns “moral” and everything has a strong potential of going south).

I’m sure I’m not making my point as clear as I might like, yet I don’t think we’re all that far apart on the key points of this discussion. I do think we have different understandings of some of the words we are using that makes it look like we differ more than we do. I agree with Marco that aesthetics and ethics are close cousins. It would seem to me that art itself is one way of coming to agree (since we experience the world as separate) that we are of one mind (overcoming the perceived separation and recognizing our wholeness) about whatever it is we are trying to figure out about the value of our existence (which I think is what we are all ultimately trying to do).

Still, I hope this all makes at least a little more sense than my last post.

WARNING: SUPER LONG POST!

This is an important question, also one which I am trying to figure out in the context of “heart-reading,” vibration, and other stuff, so I’m happy to take some time this morning/afternoon and explore it with you and whomever else is interested. But, I think it’s high time we move out of our theoretical perspectives, and move into actual works of art, which we weirdly haven’t done yet, which to me is probably some kind of evasion on our parts. So, I thought this morning in the shower: what poems should we look at? And, I decided I wanted to look at the work of two poets, also African-American, male and queer, both mostly 20th century (Reginald Shepherd passed away in 2008). Before we look at the poems, though, maybe a quick introduction, to explain why I chose work by these two poets.

I think it’s important, especially in our very intense “cultures wars,” which manifests in different ways in the various debates in the poetry and literary worlds, for poets from various backgrounds to discuss the work of poets from different backgrounds - with care, conscientousness, awareness of differences, but also awareness of authentic, actual (not wispy or too new-agey or assumption-laded or whatever else) commonalities . For some on IC, this might sound obvious; to others, it might not. But there is a very apparent cultural context in which such a decision, move, belief, value - to write about, engage with, deeply think about works by authors from different backgrounds and cultures, and write about such authors/people, whether in prose or poetry - is considered problematic, or appropriation in a negative sense. From my perspective (I would love to hear what others think), these interpretations are taken too far, and suggests sort of silos based on identity that I think are utterly counter-productive and even disingenuous in a way. Of course, such cultural crossings should be done with care. But also of course, they should be done, practiced, performed, etc., if we are to acknowledged the truth that there are very many commonalities that do ultimately unite us.

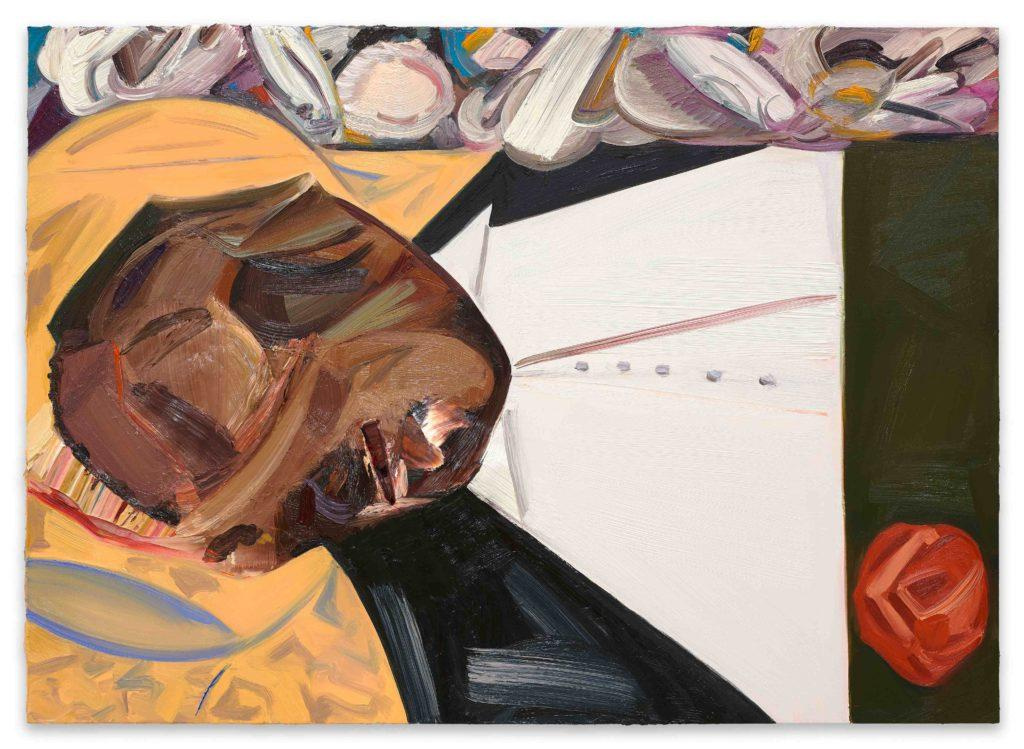

For people who are new to these issues around appropriation, it could be good to read something about these debates. For example, the “Open Casket” controversy - here is a link to the Wiki page, although of course that’s only the beginning. (The controversy involved a White (and Jewish) artist, Dana Schutz, painting a portrait of Emmet Till, the 14-year-old African-American boy who was horribly and tragically lynched in Mississippi by two white men in 1955.) For quick reference, here is the painting:

It would also be useful to have an awareness regarding the very intense controversy that happened in 2015 in the poetry world, involving the “Conceptual Poets” (link to a definition of conceptual poetry) Kenneth Goldsmith and Vanessa Place, in the context of appropriation. Here is an article about these controversies in the Los Angeles Review of Books, an online magazine I personally like and find even somewhat rigorous, though I’m not sure I totally agree with the author’s take; here is another article by the poet and critic Aaron Kunin that I personally think is more accurate - he actually uses the term “aesthetic value,” thus relevant to @achronon’s invocation of value (ethical in Ed’s case) in his last post - though I’m always open to hearing what others think.

This framing can go on forever. I’m hoping these cases might be illustrative and somehow somewhat representative, at least for those who are new to these important controversies and debates in the art and poetry worlds and beyond. When I choose to talk about the work of two African-American poets, who are also male and queer (Hemphill also lived with AIDS), this takes place within the context of these debates. My choice should in some ways express where I personally fall in these debates - I do think artists and critics should be free to explore the world, the self, creativity, etc. through whatever lens they feel is appropriate, even if said lens involves the experience of a different person, group, culture, society, etc. I find the exclusive emphasis on identity politics and difference, without any recognition of real commonality, to unfortunately miss the point, and sometimes even devolve into its own vicious form of ethnocentrism. That’s my take, at least. (I just realized I haven’t stated that I am a white, Jewish, heterosexual, cis-gendered male, among many other things.)

So: we were talking about evaluation. Let’s look at two poems, so that I can show what I mean, instead of theorize about it. I’m going to share a poem first by Essex Hemphill. Here is a short introduction to the poet, performer and activist on Poetry Foundation’s website; here is a link to an anthology of writings by Black gay men that Hemphill edited, at Internet Archive (you can create a free account and check it out). Also, the poet Danez Smith recently wrote an essay in the NYTimes which is a moving love letter to Hemphill here.

I recently borrowed from the Internet Archive a book by Hemphill called Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry. It is a collection of prose and poetry published in 1992. The book opens with a poem called “American Hero,” which can be read below. (Placements of poems in books of poetry, or poetry and prose (sometimes called sequencing), should be thought about it and taken into account, especially poems that open and close a book. As this poem opens Ceremonies, I think it’s a good place to start our discussion about evaluation).

If you’ve read the poem, what did you think about it? Did you enjoy it? What did you enjoy about it? Were there any formal features that stood out - word choice, enjambment (the continuation of a sentence without a pause beyond the end of a line, couplet, or stanza.), syntax? How did these features help or not help you to experience the poem? How did you experience the poem?

The poem is in both the present and past tense, and seems to be a memory (suggested by the past tense in “I scored / thirty-two points in this game”) of a thrilling experience during a basketball game (backboard, net, ball, score, etc.). Yet I think this poem serves as a good example of a few things, though here we can focus on aesthetics/ethics, figurative language, as well as (if we have time) the role sincerity plays and does not play in poetry. Let’s start with ethics and aesthetics. What are some aesthetic aspects of the poem? “Shimmering club light” is interesting, as a sort of transposition of the unmentioned basketball court into a new environment/context. Also, “Choke it” - the undertone of violence implied by the phrase - is an intriguing way of talking about a basketball sliding through the net. There is some alliteration - the “s” in “slick,” “sweat,” “squinting,” “slap,” “slam,” and so on. And there is a “volta” in the poem - volta refers to a shift or change in the poem towards or into a different direction, here signified by the word “But.” Here the volta involves a recognition, colored by a sort of sober sadness, even weariness, that the feeling of happiness, excitement, joy, aliveness, described in the above lines in regards to this experience playing sports and feeling a sense of community and genuine pride would, in a different context - “towns, / certain neighborhoods” - not actually happen, where no cheers would be heard if the speaker moved or lived there.

What are the ethical aspects of the poem? I think the volta is at the heart of this question - Hemphill is raising the important point that, in one context he feels happy, an “American Hero,” and in another context - presumably White, or heterosexual, or cis-gendered, etc., though this is not made explicit and left more open - he is not.

Okay, we have tried to offer a balanced reading of the poem - what is essentially an “analysis.” For those unfamiliar with analysis and evaluation, here is educational theorist Benjamin Bloom’s famous and ubiquitous-in-education-programs “taxonomy”:

Like Maslow’s famous hierachy, Bloom’s taxonomy is a movement from what is more fundamental to what is more significant. In this sense, evaluation is actually harder and more significant than analysis - it requires actual judgment, (judgment has connotations of prejudice, or “judging someone,” but that’s now how I mean it here). To actually evaluate a work of art requires some expertise. The person doing the evaluating - a critic or scholar, let’s say - must compare the work of art to pretty much every work of art he or she has ever seen, conscioiusly and/or unconsciously, and reach some sort of conclusion, even a tentatively authoritative conclusion, about the value or significance of said work of art. This essentially involves a deep, informed, wide-ranging and subtle act of comparison (depth and width), and the comparison is used in the service of a more conservative (another loaded word, though I am not referring to politics here - more in this sense of “conservation”) purpose, i.e. to make an argument about what should be essentially preserved, saved, returned to, because it has enduring aesthetic value beyond one’s time and place and culture. Now, of course this is in many ways a total crap shoot. In this way, it’s fascinating to read contemporary reviews of Whitman - in some ways, many people just were not ready for Walt’s poetry. But take Samuel Johnson’s estimation of Shakespeare - that, conversely, has endured. So it’s interesting to think about.

I should say now that evaluation is not really practiced very much today. It was in the past - F.R. Leavis is probably a good example of this, and of course Bloom - but postmodernism, and especially egalitarian postmodernism, resists hierarchy, so the idea that there are actual qualitative differences between works of art that makes one artwork better (and not just different) is often not talked about.

Now let’s return to Hemphill’s poem, through the lens of evaluation. Is it any good? Compared to what has been written in the past, in poetry, does it have value? Well, as we covered in our analysis, it has some aesthetic value and some ethical value. Does it have any lasting value? Here is where I would say, “no,” this poem does not have enduring aesthetic value. It is interesting and important as one gay Black man’s experience, but this is primarily a sociological and ethical valuing. Aesthetically, the poem is pretty unexceptionable. The language is somewhat staid and tired - “The crowd goes wild,” “I scored / thirty-two point this game / and they love me for it.” The form and content do not seem totally necessary - could this poem work in the same exact way as a prose poem, or just as prose? Is there anything really aesthetically new about this poem? Again, I’d have to say no - there have been many poems written just like this one - not identical, of course, but in the same sort of vein, tenor, mode, figuration, language, arrangement, formal concerns, etc. Perhaps its stands out sociologically, as a pioneering and very courageous queer Black man with HIV writing about an “American Hero.” And yes, of course, there is pathos there. But at the level of aesthetics, this poem is pretty run-of-the-mill. (Please feel free to disagree with me here.)

I need to leave soon to eat lunch, so I’m going to share a second poem now, but I might not have too much time to discuss it, at least for now. Here is a poem by Reginald Shepherd - an introduction to his work can be found here, as well as a great long quote from Shepherd himself about his poetics and poetry. Shepherd was also African-American and queer. Yet his poetry, unlike Hemphill’s (or at least what I’ve read of Hemphill’s, which is admittedly not much so far), does have some lasting value, I would argue. Here is a poem called “The Friend”:

Can you feel - do you experience - the difference between “The Friend” and “American Hero”? Shepherd’s poem is richer, more complicated, more demanding, more difficult, more intriguing. It demands more attention, and rewards more attention. For example, what does it mean for a queer Black poet to describe himself as “posthumous”? Not only once, but twice? What is happening in this poem? How do you understand it? I would argue, as should be obvious by now, that in this instance, Shepherd’s poem has more aesthetic value than Hemphill’s. I’d love to take some time and offer an analysis of “The Friend,” but unfortunately I don’t have time right now. Still, maybe this is a good thing - for, if you have time, whoever is reading this, really look at, read, experience, absorb, both poems. Think about what they are doing, how they are doing it, what they mean. Then, don’t be afraid of doing this - compare them. Are they different? Similar? How so? I think that if we are honest, we’d find that Shepherd’s poem, in the context of evaluation, is richer and more aesthetically significant than Hemphill’s. And, along with this, that this is an important insight, and that we should be able to make and argue for such evaluations, as we are all essentially custodians of culture, and what we save and judge as lasting will have an impact on our own culture, as well as those who come after us.

Whitehead has an interesting take on “evaluation” (see “Process and Reality”) - he talks about a somewhat different idea, which he calls “valuation”. Valuation may be thought of as a process of “being present”, or of values manifesting themselves within a process of (self) discovery/emergence - Whitehead never uses the term “self” so I am distorting his point of view here, he views the self, if he addresses the question at all, as a collection or “nexus” of events. I’m sure Whiteheadian scholars will cringe at this description, but it gives some sense of what Whitehead is trying to get at. The point is that “evaluation” requires a subject-object split to undertake, which is why I am generally unhappy to be involved in any kind of evaluation exercise (and yes, I am a teacher, so this position is problematic!). Valuation, on the other hand, requires no such split - Whitehead’s process philosophy is a non-dualistic understanding of the world. Valuation emerges from events as they manifest themselves, or rather, it is part of the creative act which engenders events. Indeed, Whitehead’s aesthetics is an ethics, and vice versa (although he is not the easiest philosopher to decipher!).

Here is Whitehead himself on “valuation” : “But though these three characteristics are included in a valuation, they are merely the outcome of the subjective aim of the subject, determining what it is itself integrally to be, in its own character of the superject of its own process.”

Interestingly, Whitehead uses the term “integral” though differently from Gebser, or Wilbur (Whitehead’s work came earlier) and he also emphasizes “intensity” in a way that parallels Gebser.

In the above quote, you talk about the “transverbal heart”. I’d love to know more of what you mean be that…

Andrew, I’d like to thank you twice: once for the Warning (yes the post is LONG), but also for what you have said. I’ll be honest: I read your post, but I don’t know to what extent I can respond.

First, my excuses: I participate regularly in the CCafés, because I can, and because I get a lot out of them. The timing works for me here in Germany, and, unlike some of the other participants, I care less about the topic than the opportunity to meet up with others “head-on”, so to speak. Consequently, the forums (before and after) demand a bit of attention and time. Second, I let myself be willingly talked into participating in a reading of Bellah/Joas’ _The Axial Age and Its Consequences _, which is anything but an easy read, but because the subject and the participants make me think it would be worth my while to do so. Third, though retired, my time is not my own, just like the rest of you who find themselves in the thick of life. From my vantage point, it doesn’t get “better”, it just gets to be more. You don’t gain anything timewise just because you’re retired.

On the other hand, there is lots I’d like to do: write, think, cogitate, ponder, meditate, reflect, and more, but since there’s only 24 hours in the day, it requires one helluva lot of juggling. The older one gets, the less vibrant one’s reflexes and timing becomes. I like to think I do what I can, but it’s never as much as I would like, and I always have a guilty feeling that I’m neglecting things I should be attending to. Like your post. I’d like to do more, but am having trouble managing all I would like these days.

Be assured, I admire your approach, your enthusiasm, your devotion. I would like to be able to engage poems in the way you describe. I grew up during the “close reading” phase of criticism. I was back at (a German) university when hermeneuticism was battling it out (literally) with critical rationalism and the scientification of literature studies, and the humanities in general. I cared – and still do – about whether art matters and whether there is anyway that we could make more people aware of and receptive to it. My first degree was in teaching, my second closely aligned, and I got sidetracked thereafter, but one’s first love is always one’s true love.

What I’m saying is that while I sincerely appreciate you wanting to get into the nitty-gritty of what’s behind our little discussion here, I don’t think I have the time to do so. Others have their own schedules of course, but what you would like to do takes time.

Don’t get me wrong … it would be time well spent. I see what you are doing as an extension of that close reading I mentioned earlier. That general direction is where I was headed during my studies in Germany. The discipline took a side road; I got hijacked on another road; and it appears that we are now back on a reasonable road toward getting back into the art/literature aspect of texts.

One of the things I like about the Germans is that they don’t really make a distinction between text genres. If you’re good with words in your field, you’re worthy to be called a _Dichter _ (see Cosmos Café [7/9] - Reading and the Body - #15 by achronon). The Germans don’t make the finer distinction Anglos do, between reporting, non-fiction, prose, and poetry. This is one of those cases where less is more. What you are advocating for is, at least as I understand it, more engagement (in every sense of the word) with the text … experience the text … pay attention to that experience. I couldn’t agree more.

But … there is this time thing. Two poems wasn’t starting small. Two poems by black persons wasn’t either. Throw in “male” and “gay” and we’re getting off the charts. How unsmall can it get!? Each of these qualifications adds a dimension to the interpretation, and I don’t mean “the” in any literal or limiting (like, to one) sense of the word. In my mind, there is a text dimension, the sub-literal, if you will: an artifact, words one a page, hand-written or printed, only words. But there was a time, and a place at/in which that happened. And there was a particular person, which a particular background and path of development who encounters these words and thinks it might be a good idea to give them more than passing consideration: the text dimension.

But then there is the meaning dimension to consider. How these words relate to one another. The syntax of each and every subunit of a sentence in that text. This is, I believe, particularly relevant in poetry (though I find a lot of what I’ve read over the past 15-20 years anything but parsimonious, what specific sense is being made. And then we have the personal position of the writer, the one putting the words on the paper or hard disc, or their sexual (or other) preferences, how important their identity is to them, not to speak of the social (neighborhood to nation) and cultural context in which they live. It’s more like making an onion, not peeling one. That takes time and attention. I’m missing the former.

My point, albeit belated, is that I’d really like to get into this, but not exactly now. Yes, I’d be willing to follow along on any discussion that arose here, but a direct engagement of the task-at-hand exceeds my capacities at the moment. Of course, this doesn’t preclude anyone else from engaging the topic at this level. That would be great. I always have the option of following the discussion thread. The asynchronicity challenges some, but sometimes it’s the slowest way to still go.

I knew Essex Hemphill from the struggle, and he was in my view, a product of a certain time and place. He had a free style homo-erotic feel , political but the tone was primarily elegiac. I remember being shocked by a PBS show dedicated to him, his lyrics were quite over the top. His death was a painful blow. So many talented young people we lost.

I would compare this poem, American Wedding, which certainly captures his personality better than American Hero, which is a weaker poem. Essex is, in my view, the spiritual offspring of Whitman. And I also hear echos of a much older love story. Here are some selected passages from the Old Testament

…the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul…

3 Then Jonathan and David made a covenant, because he loved him as his own soul.

4 And Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that was upon him, and gave it to David, and his garments, even to his sword, and to his bow, and to his girdle.

And later…

David arose out of a place toward the south, and fell on his face to the ground, and bowed himself three times: and they kissed one another, and wept one with another, until David exceeded.

42 And Jonathan said to David, Go in peace, forasmuch as we have sworn both of us in the name of the Lord, saying, The Lord be between me and thee, and between my seed and thy seed for ever. And he arose and departed: and Jonathan went into the city.

And in David’s great lament after Jonathan’s death…

25 How are the mighty fallen in the midst of the battle! O Jonathan, thou wast slain in thine high places.

26 I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan: very pleasant hast thou been unto me: thy love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women.

27 How are the mighty fallen, and the weapons of war perished!

Here is a performance of American Wedding

The Friend is a new poem for me and I like it. It reminds me of a dream I had last night. I read this poem telepathically.

I am riding in a train through a vast landscape. I am sitting next to a woman and I tell her about an important event. “My first lover, Terry, has replaced my father, as the driver of this train. Terry died in 1984.” I ponder this new arrangement. I am aware that both my father and Terry are dead but in this new arrangement I am delighted that he is alive. This I find very wierd, paradoxical. My father, a monster, is no longer, running the train.

Then I see a movie of Terry and myself, moving through a misty landscape and I get a powerful sense of renewal.

So, black, gay, straight, whatever…I am interested in comparing the best of the writing of anyone I am comparing and I register affective and mostly invisible backgrounds that make up these dreamscapes. So this is where I imagine this poem is coming from, not exactly but sort of… I do like both poems but for very different reasons. I would not care to evaluate either one, any more than I plan to evaluate tonight’s dream.

I am interested, however, in comparing affective states, as they move around in different contexts, and locations, across times and spaces, in myriad tones and through many voices and fade away.

Thanks, Andrew, for opening this liminal zone, for us to play around within. By the way, I did a riff at the last Cafe on the story of Jonathan and David, so I sense we may be on a continuum, much like a twist in the Mobius strip. I am less able to make propositions about external events out there, and so I resonate, vibe, appreciating the boundaries between concepts are getting pretty thin. I am, as an elder gay man, enjoying how light I feel, as if I have finally come to terms with, and have truly honored the might dead!

Anyway, I am just starting to model my own symbolic landscape. Of course, my symbolic landscape doesn’t belong just to myself. I feel I am a consortium of intelligences constantly creating new alliances.

Thank you, John. I love hearing from you. It’s always interesting to hear about dreams and telepathy, and I also really, really loved the Old Testament quotes. Are they from the KJV? I have the Oxford KJV in my “Amazon cart,” and I want to order it soon when I have enough money. I was reading a newer translation by Robert Alter a few months back, but actually found the poetry translations really disappointing and clunky-sounding, reminiscent of a poet whose work I often cannot really tolerate, named Charles Reznikoff (I just feel reading him that I am in Hebrew Sunday School or something, and a teacher wearing brown pants and suspenders is droning on about Old Testament legalism). After reading those Alter translations, I took out the Oxford KJV from the library and read a bunch of psalms and Ecclesiastes and I was like, “yes, yes, yes - this is the stuff!” (Alter is not all bad - I do like his narrative translations, especially on King David actually.)

After reading your post, I tried to find a poem by Ashbery where he talks in an interesting and funny way (Ashbery can make me laugh out loud) about telepathy. I kind of think he had some experiences along those lines, though I’m speculating. I’m glad to hear you feel light - what a beautiful thing, to actually come to terms with something! I think I’m also coming to terms with things, here in my new apartment, which is not fancy, but it has a sun room which makes me happy, and a quality of unclutteredness that I enjoy, that was not part of my former life.

Apropos of mentioning J.A., here is a great reading he gave of a funny poem I’ve always liked, called “My Philosophy of Life.” It’s interesting to notice where and how he pauses - his readings are always really great, and some people have claimed that they only understood his poems once they heard his voice reading them.

Yes, KJV is the one I grew up with. I have looked at the American Standard but find it very dry. But it is good to check out different translations for obvious reasons. I do not share your dislike of Reznikoff. I find him amusing. And thanks again for the Ashberry.He is very clever here. Although, Ashberry and Essex Hemphill both identify as gay there is an enormous difference in style. And style, as a great drag artist once said, is what your friends like about you and doing it on purpose.